There’s a small mathematical claim that reliably starts arguments in comment sections, classrooms, and late-night group chats:

Not “approximately.” Not “close to.” Equal. Exactly.

If that sentence makes you feel a flash of irritation-good. That reaction is the entire point. This is one of those concepts that feels like a cheat code, and the reason it’s so click-worthy is simple: it forces you to examine what numbers are.

Let’s walk through why it’s true, why it feels false, and what this tiny controversy reveals about infinity, decimals, and the foundations of real numbers.

⸻

Why this triggers people

Most of us grew up with a powerful mental model: decimals describe numbers like a measuring tape.

• is a little less than .

• is even closer.

• is closer still.

• So must be “a tiny bit less” than .

That last leap is the trap. In everyday language, “a tiny bit less” sounds like it should exist. In real-number mathematics, it doesn’t - at least not in the way you want.

The difference between “always less” and “never reaching” is subtle, and infinity is merciless.

⸻

Proof #1: The one-liner that ends most debates

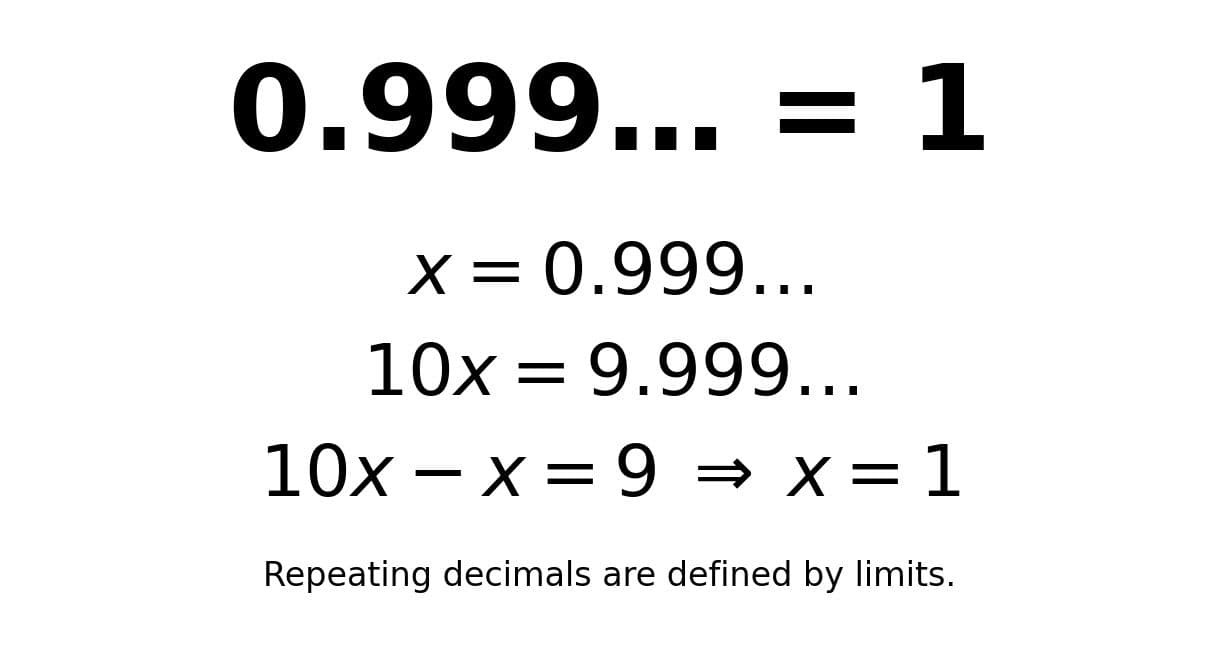

Let

Multiply both sides by 10:

Now subtract the original :

The repeating tail “” matches perfectly and cancels:

So .

This feels like magic because we used an infinite decimal as if it were an ordinary algebraic object. That’s allowed because repeating decimals are not mysterious strings; they represent real numbers defined via limits (more on that soon).

⸻

Proof #2: Limits-what really means

The notation is shorthand for an infinite sequence of

approximations:

The approximation is:

Because , and so on.

Now ask: what number does this sequence approach?

So by definition,

This is the cleanest interpretation: is not a number you “never reach.” It’s the number you reach in the limit - and that number is exactly .

⸻

Proof #3: A geometric series (the “infinity adds up” proof)

Write the repeating decimal as a sum:

This is a geometric series with first term and ratio , the sum is:

So:

Same result, different lens: infinity can produce finite values, and repeating decimals are exactly that.

⸻

“But there must be a tiny gap!”

Here’s the common objection:

If isn’t less than , then what is the difference ?

Let’s compute it using limits:

So the “gap” is . There is no positive real number that fits between them.

At this point people often try to invent a number like , imagining infinite zeros followed by a at the end.

But an “end” doesn’t exist. That’s what infinite means here: there is no final digit where you can place that . A decimal expansion with infinitely many digits does not have a last position.

So “” is not a real number in the usual decimal system. It’s a symbol that expresses a desire, not a defined quantity.

⸻

The real reason: decimal representations are not always unique

Here’s the punchline that makes everything click:

Some real numbers have two decimal expansions.

The simplest example is:

And also:

More generally:

Any terminating decimal has a twin representation where you subtract one unit in the last nonzero digit and then fill the rest with 9s.

This is not a bug. It’s a feature of the base-10 positional system combined with infinity.

Think about how fractions work:

- Different strings, same value.

Decimal expansions are similar: they are representations, not the numbers themselves.

⸻

A good mental model: zooming in forever

Picture a number line. Place on it. Now place , and so on. Each one is to the left of , but they’re getting closer.

If you zoom in around , you can always find a tiny interval where is noticeably left of . Zoom in more, and you need 0.999999. Zoom in more, and you need even more .

But in the limit of infinite zoom, there is no remaining distance. The sequence collapses onto the point .

This is what real numbers do: they complete the number line so there are no gaps left behind by “approaching forever.”

⸻

“Okay, but is it always true?”

In standard real-number arithmetic, yes.

However, if you step outside the real numbers into exotic number systems, you can talk about quantities that behave like infinitesimals-numbers greater than but smaller than any ordinary positive real number. In such systems, you can make sense of “a tiny gap.”

But that’s not the decimal system you use in calculus, engineering, physics, and basically all mainstream mathematics. In the real numbers, there is no positive real number smaller than every . The only number that fits is .

So in the mathematics that powers your laptop, bridges, and power grids:

⸻

Why this matters (beyond winning arguments)

This is not just a party trick. It’s a gateway to deeper ideas:

1) Infinity isn’t a place you reach - it’s a process you define

The dots in don’t mean “keep going, and you’ll never arrive.” They mean “define a number via a limit.”

2) Representation vs reality

Decimal strings are like names. Two names can point to the same person.

3) The real numbers are built to remove gaps

A huge part of modern mathematics is the idea of completeness: every Cauchy sequence converges. The sequence must converge to a real number - and there’s only one candidate: .

4) It explains rounding “mysteries”

Ever seen a calculator show something like ? That’s floating-point representation, not real arithmetic - but the underlying theme is the same: numbers and their encodings are different things.

⸻

A quick FAQ for the comments section

“Isn’t just very close to ?”

Close, yes. But in real numbers, “infinitely close but not equal” doesn’t apply here. The difference is exactly zero.

“So is also exact?”

Yes. And then . That’s another quick route to the result.

“Does this mean math is inconsistent?”

No. It means your intuition about infinity and decimals needs updating.

“Why don’t we teach this earlier?”

Because it requires comfort with limits or with rigorous definitions of real numbers. But honestly, we probably should teach it earlier - with the right framing.

⸻

The bottom line

The statement

is not a trick, not a paradox, and not a philosophical loophole. It’s a direct consequence of how real numbers and infinite decimals are defined.

If it feels unsettling, that’s a sign you’ve found a crack between everyday intuition and mathematical reality - one of the most productive cracks you can explore.

And once you cross it, a lot of “impossible” math starts to look not only reasonable, but inevitable.