Brachistochrone: the shortest-time path that isn’t the shortest path

Imagine you’re at the top of a smooth skate ramp. You place a bead on a frictionless wire and release it from rest. The bead must travel to a lower point somewhere to the right. You can bend the wire into any shape you like. Here’s the question that shocked mathematicians (and still surprises first-time readers today):

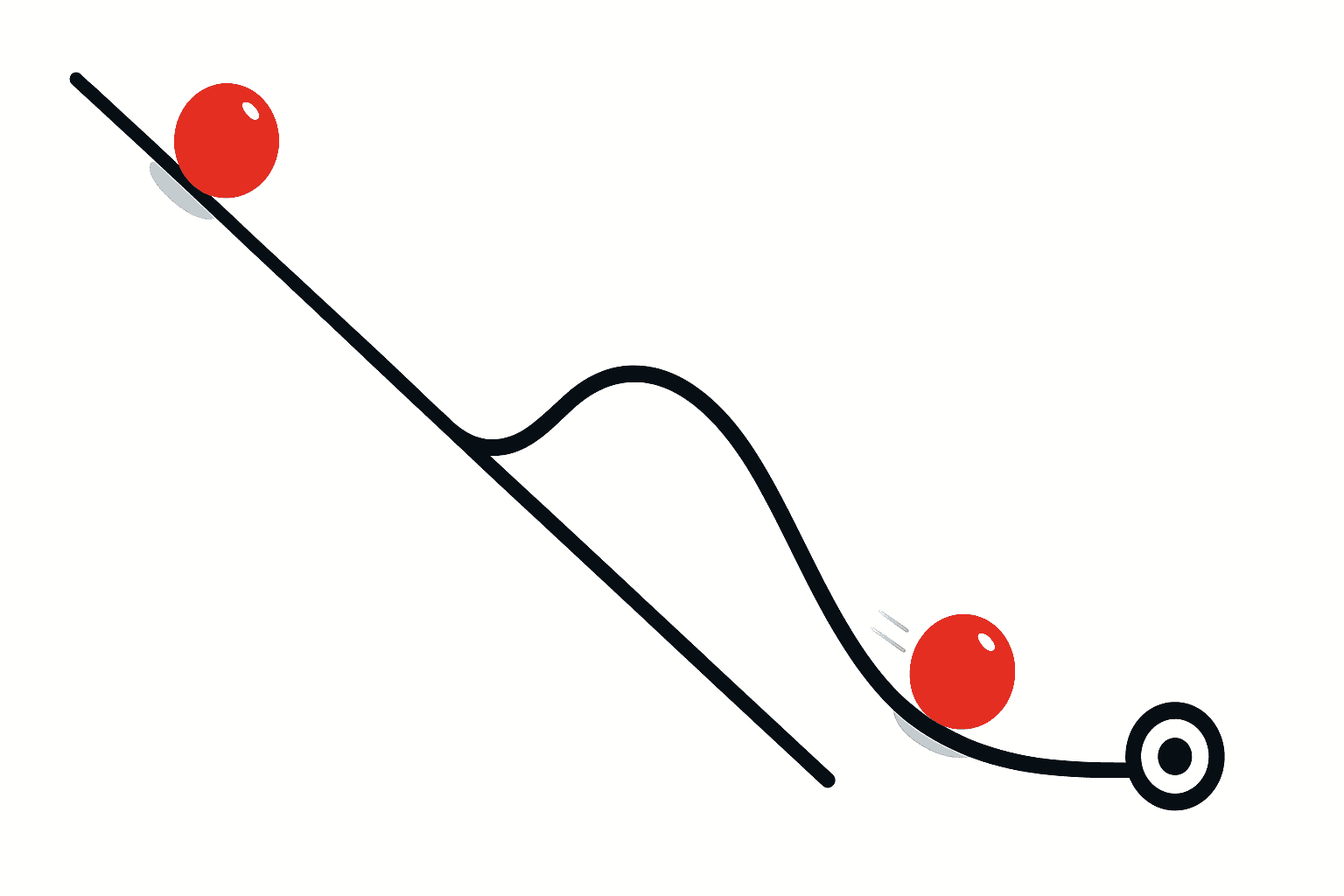

If you want the bead to arrive as fast as possible, should the wire be a straight line?

Your intuition probably says yes. A straight line is the shortest distance between two points. Less distance means less time… right?

Nope.

The fastest path is a curve-one that drops steeply at the beginning, builds speed quickly, then levels out to take advantage of that speed. The name of this problem is the brachistochrone (from Greek: brachistos = shortest, chronos = time). And its solution is one of the most beautiful “math-meets-physics” moments ever discovered: the optimal curve is a cycloid-the path traced by a point on the rim of a rolling wheel.

This is the story of the curve that beats the straight line.

Two ideas that fight each other: distance vs speed

Let’s simplify the world:

- No friction

- A bead slides along a track under gravity

- The bead starts at rest

- You can choose the track shape between two fixed points

A straight line track minimizes distance. But time depends on distance and speed, and speed depends on height.

If your track begins with a gentle slope (like a straight line that isn’t too steep), the bead accelerates slowly. It spends a lot of time crawling early on.

But if you start with a steep drop, the bead gains speed quickly. Even if the total path is longer, the bead may spend most of the trip moving much faster.

So the brachistochrone problem is basically this trade-off:

- Short distance (straight-ish path)

- High early speed (steep early drop)

The winning strategy is: get speed early, then “cruise” efficiently.

A quick physics check: speed depends only on vertical drop

This is the key fact that makes the problem solvable elegantly.

By conservation of energy (no friction), the bead’s loss in potential energy becomes kinetic energy:

Here is the vertical drop from the start (take at the start and positive downward). Mass cancels:

So the bead’s speed at any point depends only on how far it has fallen vertically-not on the path it took.

That means your control is really about how quickly you “unlock” that drop.

Time along a curve: where calculus enters

If the bead travels along a tiny piece of track of arc length ds, the time for that piece is:

Total time is the integral:

Now write ds in terms of the curve . The arc length element is:

And we already have . So the time becomes:

You don’t need to solve this integral to enjoy the story-but this expression is the mathematical heart of the problem. We want the curve that makes as small as possible.

This isn’t ordinary calculus (“minimize a function”). It’s calculus of variations (“minimize a functional”-a function of a function). Instead of finding the best number, we’re finding the best curve.

The 1696 challenge that ignited a mathematical showdown

In 1696, Johann Bernoulli published the brachistochrone as an open challenge to Europe’s best mathematicians.

This was a flex. And it worked.

Solutions arrived from a who’s-who of early calculus:

- Isaac Newton

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

- Jakob Bernoulli

- Guillaume de l’Hôpital

- others

Newton supposedly solved it overnight after coming home from work at the Mint (yes, that Newton), scribbling the answer with minimal explanation, and sending it back.

The solution they all discovered: the optimal curve is a cycloid.

What is a cycloid?

Take a circle of radius R. Roll it along a flat surface without slipping. Pick a point on the rim. As the circle rolls, that point traces a looping arch-like curve. That curve is a cycloid.

It can be described parametrically by an angle parameter \theta:

(Here increases downward if you want gravity-friendly coordinates.)

This curve has a distinctive feature: it starts with a very steep slope (almost vertical), then gradually flattens out.

Exactly what our intuition suggested might help.

Why the cycloid wins (without drowning in equations)

The deeper reason is stunning: the brachistochrone problem is mathematically similar to how light travels.

The light analogy: Fermat’s principle

In optics, light doesn’t always travel in a straight line through different media (like air and water). It travels along the path that minimizes time, not distance. This is Fermat’s principle.

When light enters a slower medium, it bends. That bending obeys Snell’s law.

Bernoulli used an analogy: imagine the bead traveling through horizontal layers where its “speed” depends on depth. Since , deeper layers mean faster motion-like a medium where light moves faster.

Then, just like light “chooses” a curved path to minimize travel time through regions of different speed, the bead “chooses” a cycloid.

So the cycloid is not just an arbitrary curve-it’s the natural geometry of “time-minimizing travel under gravity.”

A friendly comparison: straight line vs cycloid vs arc of a circle

If you’ve ever seen a demo of this, it’s almost unfair. Typically three tracks are built between the same start and end points:

Straight line

Circular arc

Cycloid (brachistochrone)

The straight line often loses because it doesn’t drop aggressively enough early on. The circular arc is usually better because it tends to dip more. But the cycloid consistently wins.

Why?

- Early steep drop = big early speed

- Later gentle slope = keep speed while not wasting motion fighting steepness

The cycloid is the “perfect compromise” across the whole journey.

A wild bonus: the cycloid has another superpower

The cycloid is not just brachistochrone (shortest time from A to B). It’s also tautochrone.

That means:

If you start the bead from any point on the cycloid, it reaches the bottom in the same amount of time.

Same time, regardless of starting height.

This sounds impossible, but it’s true (again, in the frictionless ideal). Christiaan Huygens discovered and used this property in attempts to build more accurate pendulum clocks.

So the cycloid doesn’t just solve “fastest path.” It also solves “equal-time descent,” which is arguably even weirder.

What this teaches you about “math intuition”

The brachistochrone is a perfect example of how mathematics corrects intuition-not by saying intuition is bad, but by revealing what intuition forgot to count.

The intuitive mistake is thinking:

- shortest distance ⇒ shortest time

But time is:

And speed is part of the game.

So the moral is:

In optimization problems, the best solution often comes from optimizing the right quantity, not the obvious one.

This shows up everywhere:

- In driving: sometimes a longer route is faster because of speed limits or traffic

- In computing: a “shorter” algorithm description might run slower than a “longer” one

- In learning: the fastest path to mastery often involves deliberate “hard steps” early

Steep early drop. Build speed. Cruise.

The cycloid is a metaphor you can actually use.

A small thought experiment you can try

Imagine two tracks from the same start to end:

- Track A: starts flat then drops steeply near the end

- Track B: drops steeply immediately then becomes gentler

Which arrives first?

Track B almost always wins, because it spends more total time moving fast.

That’s the brachistochrone idea in one sentence.

The “wow” ending: nature prefers time, not lines

We are raised on straight lines: shortest distance, direct path, minimal steps.

But in physics, nature often optimizes time, energy, or action-and those objectives bend reality into curves.

The brachistochrone is the moment you realize: even something as simple as a bead sliding down a wire contains a hidden geometry-one that took the invention of calculus to fully uncover.

And the answer is poetic:

The curve that beats a straight line is the curve drawn by a rolling circle.

Not because it’s pretty (though it is), but because gravity time geometry secretly demand it.

If you want to extend this post (easy follow-ups that readers love)

- Show a simple simulation (even a basic Python plot) comparing times

- Explain the cycloid visually with a rolling wheel diagram

- Connect to Snell’s law and refraction (people love “math explains bending light”)

- Write a sequel post: “The Tautochrone: the curve that makes time irrelevant.”