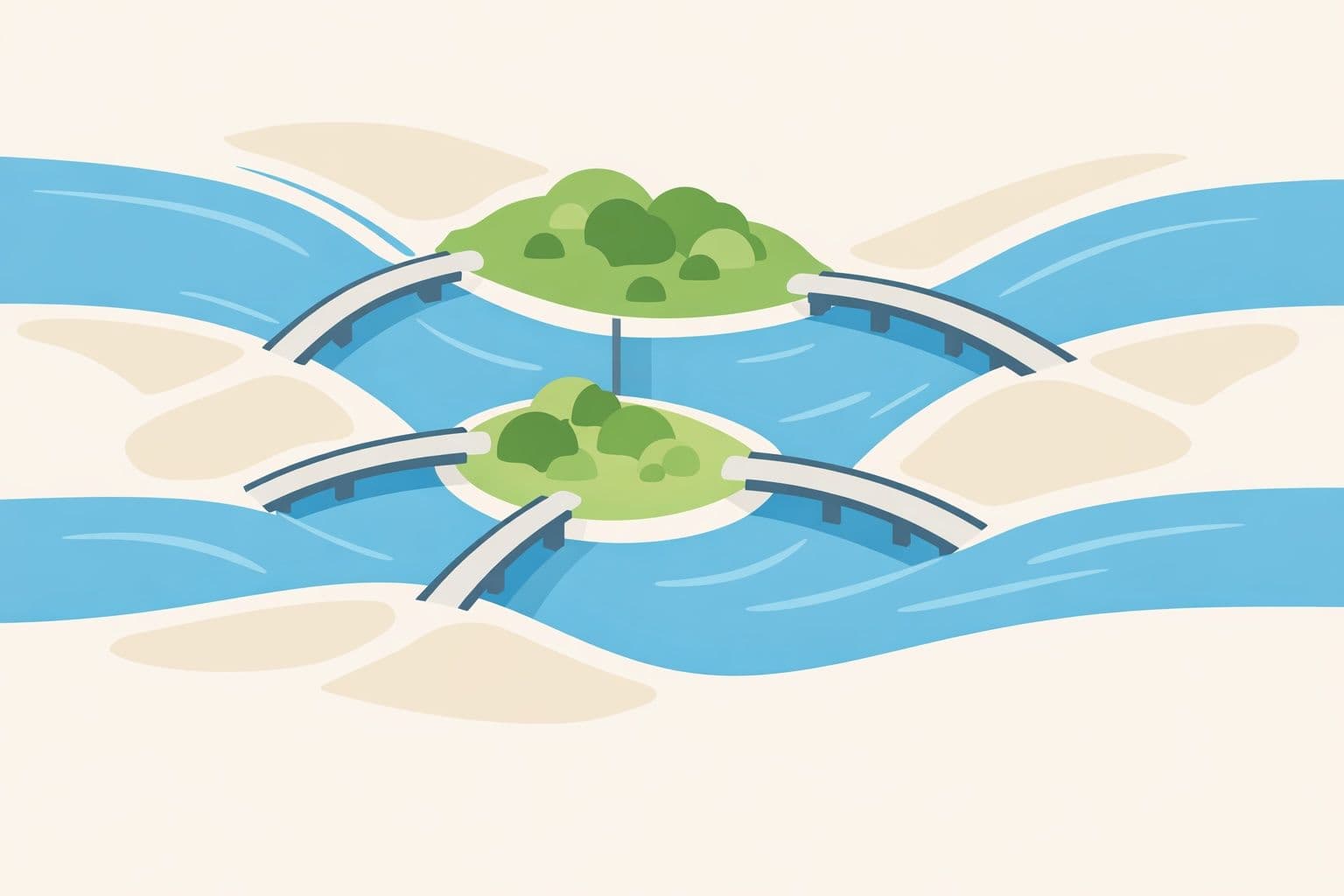

In the 1700s, the city of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) had a casual little flex: a river that split around islands, stitched together by seven bridges. Locals turned it into a challenge:

Can you take a walk that crosses every bridge exactly once?

It sounds like a tourist game. It turned into the birth of a whole field of mathematics-graph theory-the math behind networks, routing, social connections, and the internet.

The Königsberg Bridges problem (the original puzzle)

Picture this setup:

- One river.

- Two islands.

- Two riverbanks (north and south).

- Seven bridges connect these land pieces.

You’re allowed to start anywhere. Your goal is strict:

- Cross each bridge exactly once.

- No repeats.

- No skipping.

People tried. They drew routes. They argued. And the puzzle quietly refused to cooperate.

Then Leonhard Euler showed up and did something genius: he stopped caring about the exact map.

Euler’s move: ignore distances, keep connections

Euler’s insight was almost rude in its simplicity:

- The shape of the islands doesn’t matter.

- The length of the bridges doesn’t matter.

- The curves of the river don’t matter.

Only one thing matters:

Which land areas are connected to which, and how many bridges touch each area?

So he compressed the whole city into a “skeleton”:

- Each land region becomes a node (a dot).

- Each bridge becomes an edge (a line connecting dots).

That’s a graph.

This was the birth of a new idea: you can solve a real-world navigation problem by turning it into pure connectivity.

The key concept: degree (how many bridges touch a place)

In a graph, the degree of a node is the number of edges connected to it.

Translated back to bridges:

- The degree of a land area = how many bridges lead into/out of it.

Now here’s the crucial walking fact:

Every time you enter a land area using a bridge, you must leave using another bridge… unless it’s the start or the end of your walk.

That means:

- For any “middle” land area, bridge crossings come in pairs (in + out).

- So every middle node must have an even degree.

Only the start and end points can be different:

- If you start at one node and end at another, those two nodes can have odd degrees.

- If you start and end at the same node (a loop walk), then all nodes must have even degree.

This gives the famous criterion:

- Eulerian circuit (start=end, use every edge once): all degrees even

- Eulerian path (start≠end, use every edge once): exactly two nodes have odd degree

- Otherwise: impossible

The proof is in one clean punch

Let’s prove it in plain terms.

Suppose you have a walk that uses every edge exactly once.

- Each time you arrive at a node (land area), you must also depart, because edges can’t be reused.

- So arrivals and departures pair up.

- Therefore, the total number of incident edges used at that node must be even.

The only exception:

- The starting node has one extra departure (you leave without having arrived first) → odd degree allowed.

- The ending node has one extra arrival (you arrive and don’t leave) → odd degree allowed.

So:

- If a path exists, you can have 0 odd-degree nodes (closed loop) or 2 odd-degree nodes (open path).

- If you have 4 odd-degree nodes, you’re doomed.

Apply it to Königsberg: why it’s impossible

In the Königsberg bridge layout, the four land regions have degrees:

- One region has 3 bridges

- Another has 3 bridges

- Another has 3 bridges

- Another has 5 bridges

All of these are odd.

That’s four odd-degree nodes.

But we just learned:

- You’re only allowed 0 or 2 odd nodes if you want to cross each bridge exactly once.

So the answer is not “we haven’t found the right route yet.”

It’s stronger:

No such route exists. Ever.

That’s the moment graph theory is born: a real-world question answered by a structural invariant (odd/even degrees), not by brute-force searching.

Why this tiny puzzle became huge

Euler didn’t just solve a city riddle. He introduced a new way of thinking:

Strip a problem down to its connectivity and count constraints.

That single shift powers modern systems like:

- GPS routing: roads as edges, intersections as nodes

- Internet traffic: routers as nodes, cables as edges

- Electrical circuits: junctions and connections

- Social networks: people as nodes, relationships as edges

- Biology: neural networks, food webs, gene networks

- Logistics: delivery routes, warehouse networks, airline hubs

Any time you see “things connected by links,” you’re in graph territory.

A modern mini-example you can do in your head

Say you’re designing a walking trail system in a park and you want a “cross every bridge once” challenge.

You sketch a graph and compute node degrees.

- If you want a loop walk (start=end), make every node degree even.

- If you want an open walk, allow exactly two odd nodes (start and finish).

- If you see four odd nodes, you can stop early: it’s impossible.

This is powerful because it’s a fast impossibility check. No searching, no guessing, no “maybe there’s a clever path.”

Just parity.

Key takeaways

- Euler solved the Königsberg bridges puzzle by ignoring geography and keeping only connections.

- Turning land areas into nodes and bridges into edges created the first famous graph model.

- A walk that uses every edge once requires 0 or 2 odd-degree nodes.

- Königsberg has 4 odd-degree nodes, so the route is impossible-provably.

- This idea became graph theory, powering routing, networks, circuits, and modern connectivity problems.