Évariste Galois lived fast, argued with institutions, got arrested for politics, and died at 20 from wounds after a duel.

That sounds like a movie pitch. But the real plot twist is mathematical: he found the “hidden symmetry” that decides whether an equation can be solved using radicals (square roots, cube roots, and friends).

If you’ve ever wondered why there’s a neat quadratic formula, a messy cubic formula, and then… chaos… Galois is one of the main reasons you can explain that chaos with one clean idea.

A 350-year question hiding in plain sight

For centuries, mathematicians chased a simple-sounding goal:

- Given a polynomial equation (like a quadratic or cubic),

- Can you write its solutions using only arithmetic operations and radicals?

“Solvable by radicals” means expressions built from numbers using + − × ÷ and repeated roots like , , etc.

Quadratics? Easy: always solvable (you know the formula).

Cubics and quartics? Also solvable-though the formulas are famously… not dinner-party friendly.

Quintics (degree 5) and beyond? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. That “sometimes” was the nightmare.

Galois didn’t just add another clever formula. He changed the question.

Instead of asking: “What’s the formula for the roots?”

he asked: “What symmetries do the roots have?”

The big flip: stop looking at roots, look at how they can be swapped

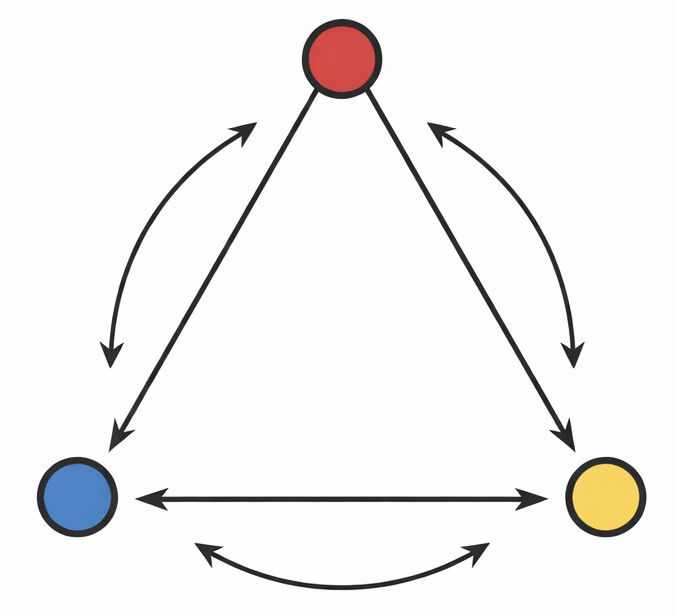

Imagine an equation has several roots (possibly complex). You may not know the roots explicitly, but you can still ask:

If I permute (swap) the roots, which swaps keep the algebraic relationships intact?

That collection of “allowed” permutations forms a group (in the mathematical sense): a set of symmetries you can combine and invert.

This is the heart of Galois theory: it connects

- Field extensions (what numbers you need to adjoin to get the roots)

- with a group of permutations (how the roots can be shuffled without breaking the underlying structure)

And here’s the punchline:

A polynomial is solvable by radicals if and only if its Galois group is solvable (a specific group-theory property).

That’s why you don’t get a “general quintic formula” like the quadratic one: the generic quintic’s symmetry group is too complicated in exactly the way that radicals can’t tame.

Worked example: a cubic where symmetry tells the whole story

Let’s do one concrete example where you can feel the method, without needing a full algebra course.

Consider:

.

Step 1: Is it irreducible over the rationals?

Use the rational root test: any rational root would be , .

Plugging in:

No rational root, so this cubic is irreducible over .

Step 2: What are the roots (conceptually)?

One real root is . The other two are complex:

where is a primitive cube root of unity.

So the roots form a neat “triangle” in the complex plane: one on the real axis, two rotated by .

Step 3: Use the discriminant to guess the Galois group

For a cubic , the discriminant is:

.

For , we have , , , . So:

.

Key fact (friendly version):

- If an irreducible cubic has discriminant that is a rational square, its Galois group is (the 3-cycle rotations).

- If the discriminant is not a rational square, its Galois group is (all 6 permutations).

Here -108 is not a square in . So the Galois group is:

.

Step 4: What does that mean in human terms?

It means: from the perspective of rational-number algebra, the roots can be permuted in any way (as long as you preserve the polynomial relations), not just rotated.

And here’s the cool part: is still a solvable group, so the cubic is solvable by radicals (which matches what we know: cubics have formulas).

So we learned something nontrivial without writing the cubic formula once.

That’s the Galois vibe.

The “night before the duel” story-and what we actually know

Yes, the legend is real-ish: the night before the duel, Galois wrote a hurried letter summarizing his ideas for a friend, dated May 29, 1832.

The duel itself is historically murky: biographers debate whether it was political, romantic, a setup, or a messy mixture. Even good sources describe the reasons as unclear.

What is not murky is the timeline:

- Born October 25, 1811.

- Died May 31, 1832.

And what matters most for mathematics is what happened after: his ideas didn’t die with him.

How his math survived: the delayed “upload” to the world

Galois wrote things that were ahead of the mathematical language of his time. Some of his submissions were misunderstood or mishandled (and he was, let’s say, not always diplomatically packaged).

Years later, Joseph Liouville edited and published Galois’s key work in 1846, and that publication became a turning point for modern algebra.

This is one of the most dramatic patterns in math history:

- A new idea appears in a world that doesn’t yet have the vocabulary for it.

- It gets ignored, rejected, or filed under “???”.

- Then someone later builds the scaffolding, and suddenly it’s obvious in hindsight.

Galois didn’t just solve a problem. He helped invent the language that makes the problem feel natural.

Why “groups of symmetries” keeps showing up everywhere

If you only remember one thing from Galois, make it this:

When something looks complicated, try to describe its symmetries.

That mindset powers:

- Algebra (field extensions, solvability, structure)

- Number theory (deep symmetry behind primes and equations)

- Geometry (symmetries of shapes, transformations)

- Physics (symmetry principles everywhere)

- Cryptography (modern algebraic structures underpin security tools)

And it’s not just “useful.” It’s a taste upgrade: once you start seeing symmetries, math becomes less like a bag of tricks and more like a coherent world.

A solvable group, very loosely, can be peeled apart in layers until you hit something trivial-kind of like factoring a complicated machine into simple gears. Radicals can handle “peelable” symmetry. They break on symmetry that refuses to simplify.

That’s why the “no general quintic formula” isn’t a random failure. It’s symmetry telling you: this lock isn’t a radical-shaped keyhole.

Key takeaways

- Galois reframed “solve the equation” into “study how its roots can be symmetrically permuted.”

- Those allowable permutations form a Galois group, a structure that captures what the equation is really doing.

- A polynomial is solvable by radicals exactly when its Galois group is solvable (a group-theory property).

- In the worked example , the discriminant shows the Galois group is , so the cubic is solvable by radicals.

- Galois died in 1832, but his ideas were published and amplified later-helping launch modern abstract algebra.